Windrush - Leave to Remain

The term “Windrush Generation” refers to the immigrants who were invited to the UK by the British government, who were trying to rebuild after World War II. These people arrived from Caribbean colonies, first docking in the UK on MV Empire Windrush in 1948.

At the time, the British Nationality Act gave citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies the right to live in the UK. In the following 25 years, nearly half a million people relocated to the “Motherland” and helped to rebuild Great Britain physically, commercially and socially. Many children arriving from British colonies arrived with their parents, or followed them later, but didn’t travel with their own passports.

As many of the British colonies gained independence, people who had come from the Commonwealth countries had become citizens in those countries and with the introduction of the Immigration Act in 1971, Commonwealth citizens already living in the UK were granted indefinite “Leave to Remain”. Furthermore, a clause in the 1999 Immigration Act protected longstanding residents of the UK from enforced removal.

In 2010, the Hostile Environment policy came into effect with Theresa May as the Home Secretary. This policy was put in place to ensure that staying in the UK as difficult as possible for non-British citizens and people who did not have Leave to Remain status. In this new legislation, the clause to protect longstanding UK residents from enforced removal was not included.

In 2013 the Home Office received numerous warnings that the people of the Windrush Generation were being treated as illegal immigrants. These individuals then started receiving Capita letters explaining that they had no right to remain in the United Kingdom, some of whom were told to leave immediately.

In 2016 the British government received correspondence from Caribbean leaders warning that many people who had spent the majority of their lives in the UK were facing deportation. After mounting pressure from the Commonwealth countries, resulted in an apology from the PM Theresa May.

Within the same year it came to light that the government was cutting off access to jobs, medical treatment, services, and bank accounts while individual cases were still being reviewed. It was also revealed that in 2010 the government had destroyed hundreds of Landing Cards that proved people’s right to remain and were making impossible demands for documentation to prove residency. Many members of the Windrush Generation who had arrived in Britain as children were wrongly detained, threatened with deportation, wrongly deported, refused re-entry to the UK when abroad and some were denied legal rights, denied benefits or medical care to which they were entitled. Many, who had paid their taxes and National Insurance contributions for decades lost their jobs or homes.

In one notable case, an individual was refused re-entry to the UK for 25 years after having traveled to the Caribbean to attend a family funeral. Another had been refused entry to the UK for 13 years, consequently not seen his daughter grow up. In one case, a gentleman with a brain tumour was made homeless and was forced to sleep on the street for years.

Members of the Windrush Generation have not only experienced a financial loss for which compensation could go some way to replace, but the psychological stress and the feeling of lost identity is irreversible.

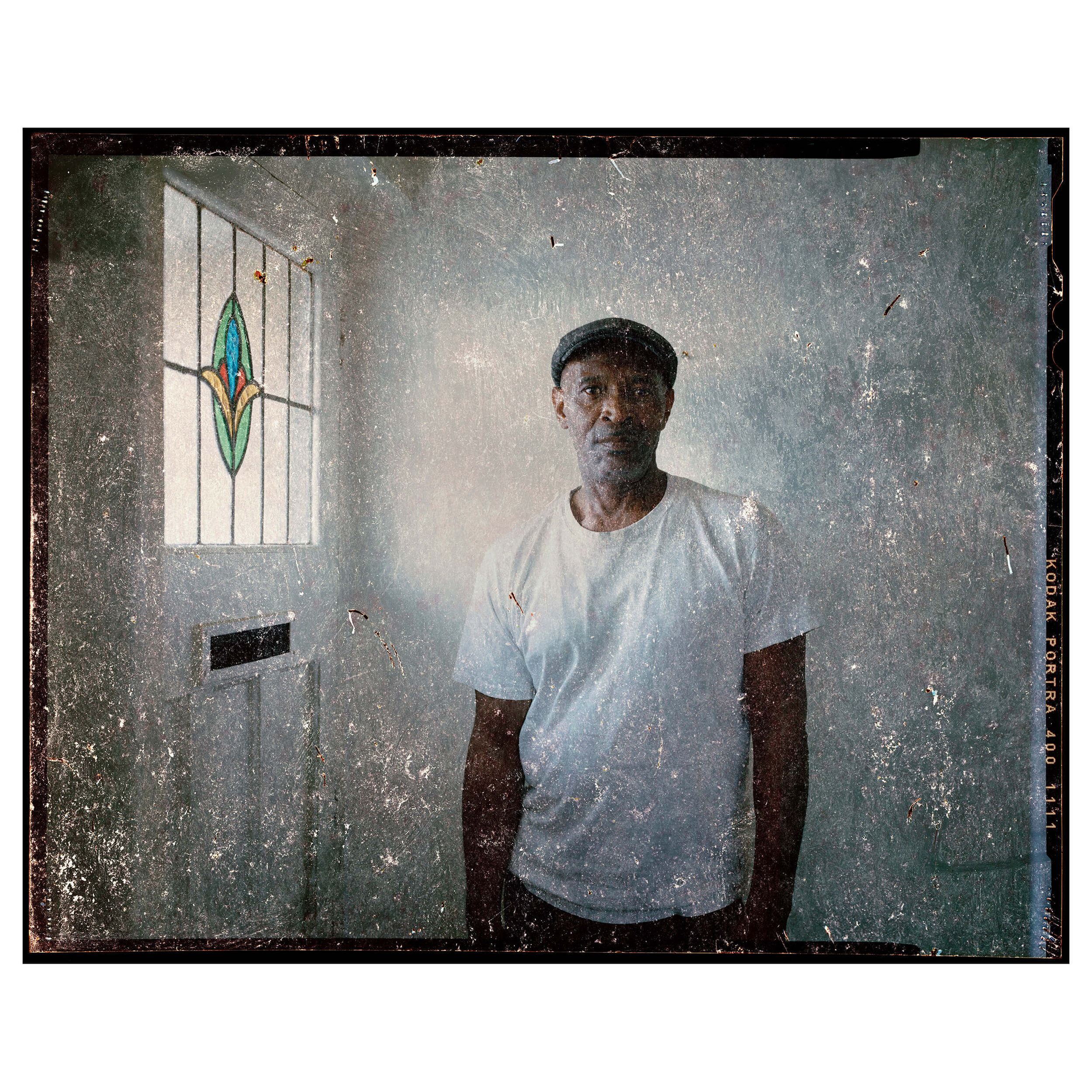

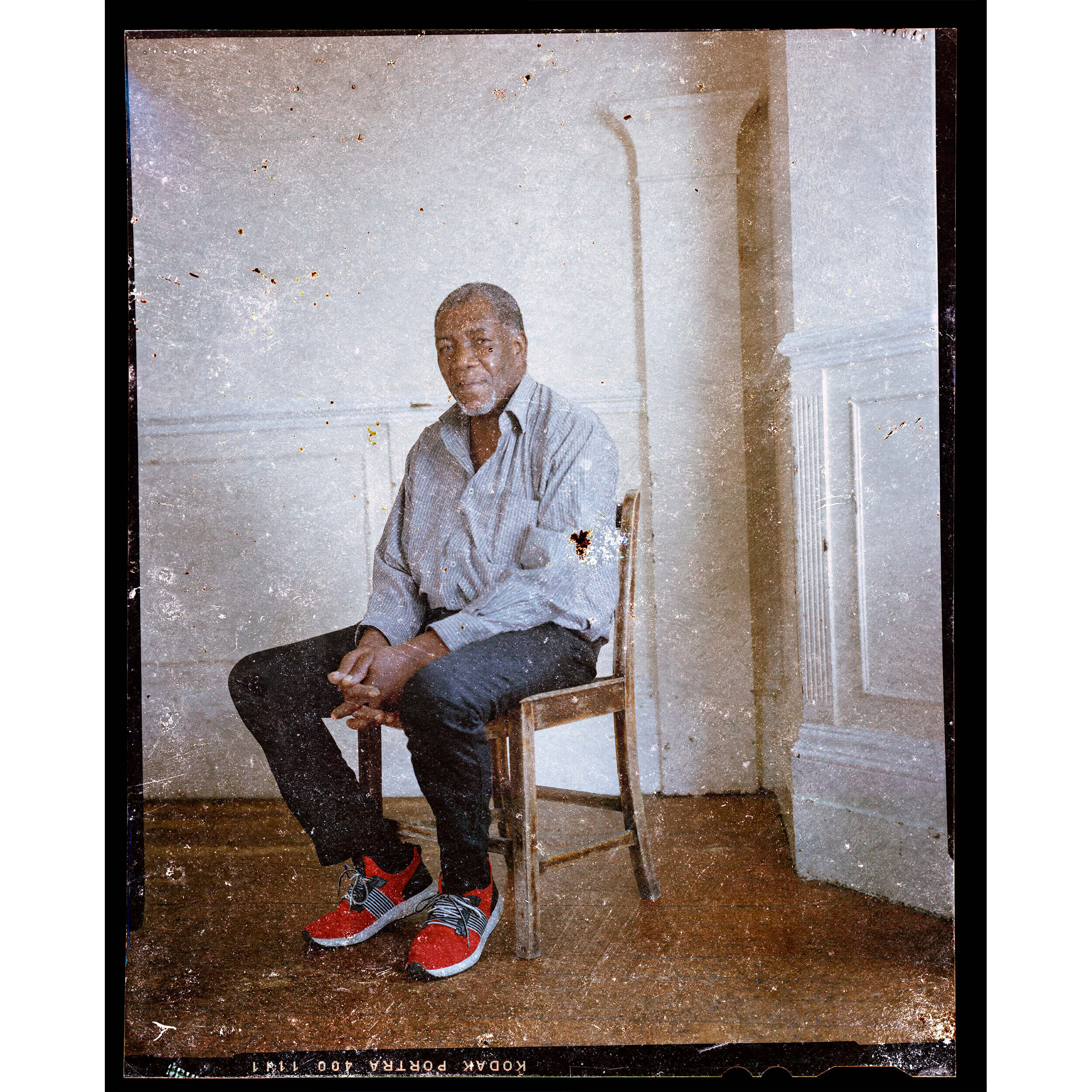

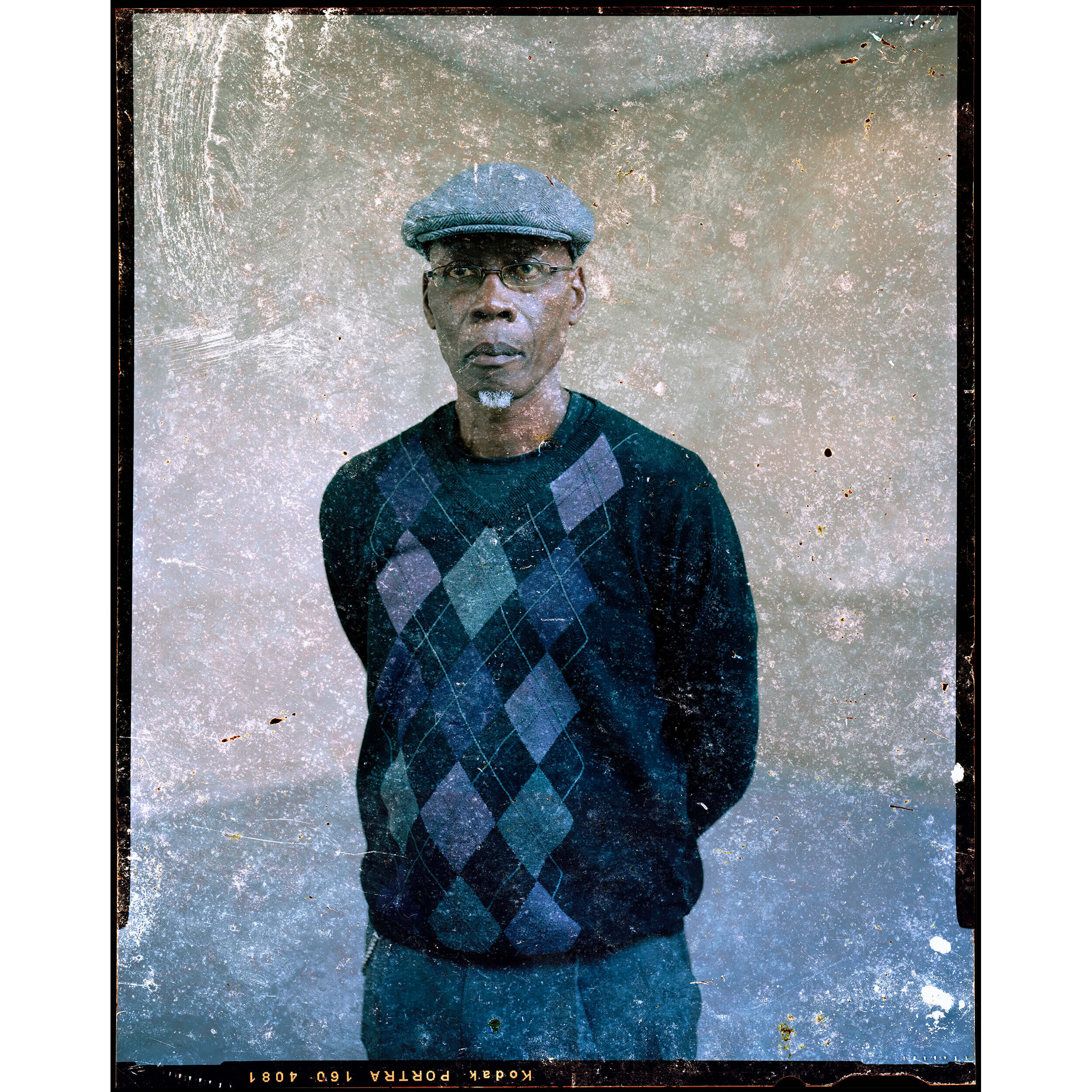

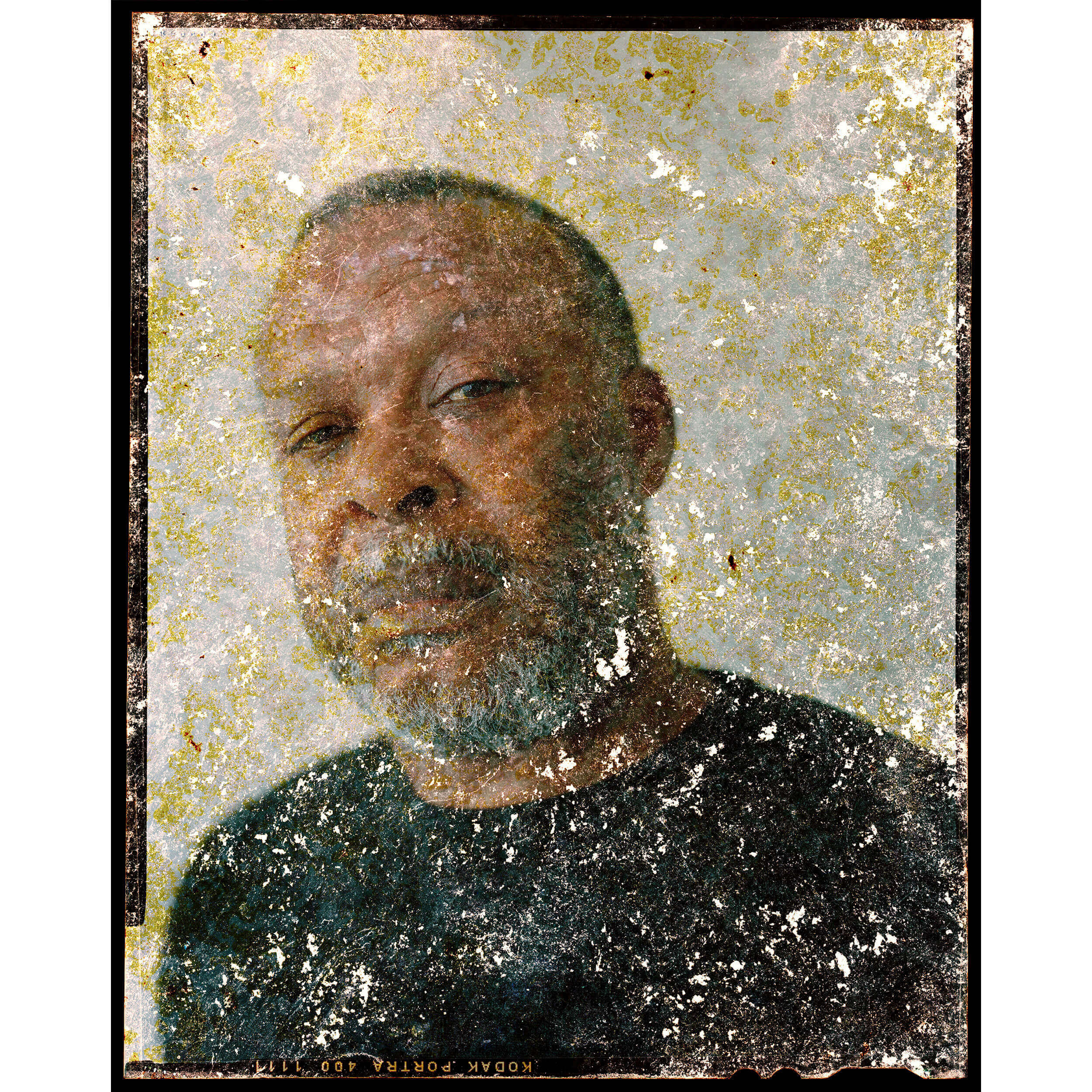

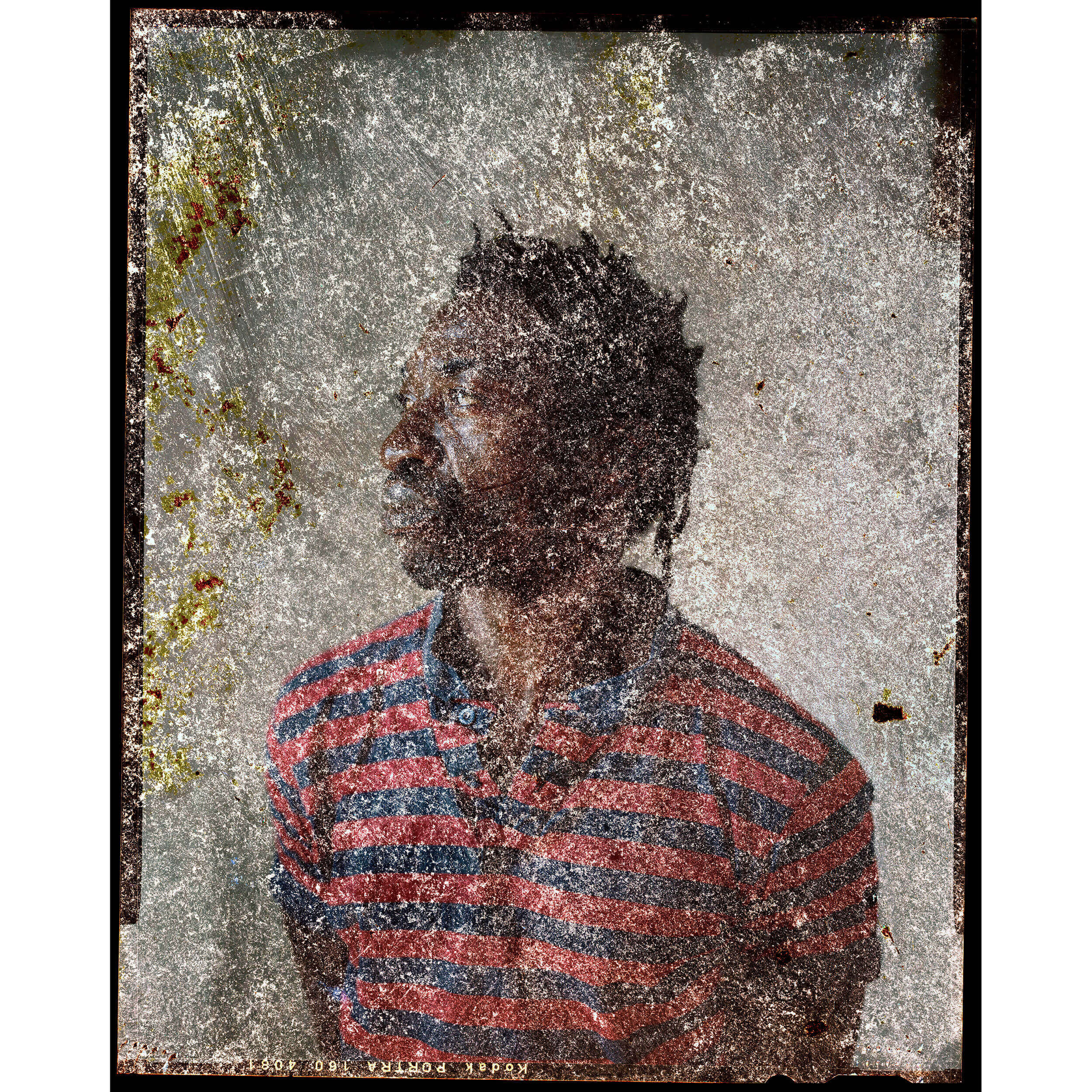

Pal Hansen has photographed the victims of the Windrush scandal on a 5X4, large format, analogue camera. The old format camera was used as a symbol of history as well as giving each image value and each frame is carefully considered. After processing, the film was buried under ground, in British soil. This process has marked the portrait with scratches and bumps made by the earth to symbolise the scars and marks that Britain has put upon the individuals after having lived here for so many years. The film then also develops a physical root in the British landscape, much the same as the Windrush generation did when they helped rebuild war torn Britain. Finally, the process of burying the film also starts to erode the film, like the government attempts to erase the individuals from the British landscape and as a metaphor of the loss identity.